Scott Douglas Jacobsen: Even if you are smart and know a way to live life, you will be wrong sometimes.

Rick Rosner: I was most famously wrong on “Who Wants to Be a Millionaire.”

Jacobsen: What was your big lesson from that?

Rosner: They were wronger than I was because if they can’t get the right answer with all their research, then the poor dipshit in the hot seat shouldn’t be expected to suss out the right answer. In almost every other case, they made it right. With me, they didn’t. It was my bad luck. I wasted much time on it. The times I’ve been wrong, the consequence has been wasted time. Einstein did all his famous work in the first half of his life.

Jacobsen: In his twenties?

Rosner: Twenties into his thirties. He was born in 1879. Special relativity was 1905, so he was 26. General relativity—I want to say, shoot, I’ve forgotten. Was it 1912? 1910? Yes, he was 30-ish, in his early thirties. He did some other stuff through his thirties, but his most famous work was in his twenties and early thirties. He worked on the Unified Field Theory for decades because nobody had created a unified field. Some people have gotten closer, using more experimental data than he had available, and further developed theories of subatomic particles.

Could he have gotten closer if he hadn’t had as big a problem with the uncertainties of quantum mechanics as he did? I don’t know. But he wasted much time later in life. You could say it was wasted. I haven’t read a strict analysis of his work in his later life, but he didn’t do anything great. He came up with the laser long before it was physically produced. I’m not sure how old he was when he did that, and I’m sure he did a lot of less famous stuff, but I also feel he wasted much time on wrong ideas, maybe.

Jacobsen: What is the big psychological growth lesson when considering Einstein and your case of suing a game show? You said decades ago, or maybe a decade and a half ago, that you regretted having the personality flaw of being too obsessive about things.

Rosner: Yes, and it also helped screw me at work because I worked on an ABC show while I was suing ABC over their conduct on the quiz show. That helped mess things up at work, too.

It also made me work harder because I realized they were pissed off at me, so I tried to work hard not to give them an excuse to get rid of me.

Jacobsen: That may have been a positive aspect. But to the general point, is the ability to admit being wrong and adapt based on that important? In other words, it is the ability to be authentically honest with oneself about the current situation.

Rosner: Yes, but it might be a national lesson for me rather than an individual one. There are tens of millions of people who can’t give up on Trump—a terrible guy representing terrible values who has been awful for America. They keep standing firm in their dedication to rotten politics. People who aren’t as misguided despair of those individuals ever giving up on Trump.

That’s similar to Germany after the Nazi era. It wasn’t that genuine Nazis changed their minds—probably most of them didn’t. The occupation forces and the newly formed government of Germany made Nazism illegal. They forced them to shut up under penalty of law. Eventually, they got old and died. I don’t know if there’s ever been a study on what percent of the Nazis who survived World War II and the post-war years of misery held onto their Nazism. That would be a tough study to do. Still, I guess that a majority of those who belonged to the Nazi party, if you talked to them in 1947 or 1951, would probably, if they were being truthful, still think Hitler was a good guy.

Jacobsen: That’s similar to the idea of Kuhn’s theory in “The Structure of Scientific Revolutions.” He says that often, for a new theory to replace an old one, you have to wait for the people who believe in the old theory to die off.

Rosner: Yes. I’m on Twitter all day, looking at the claims and counterclaims from each side. I try to be open to the other side, occasionally saying something true and accepting it if it’s a worthwhile point. That’s not the case with every point, however. For example, with Lance and COVID, he sends me studies, and I’ll look at them a little bit. But generally, almost instantly, I can see that they’re bad studies put together by people who don’t know what they’re doing or have a creepy agenda and are straight-out lying.

He sent me an article about a pro-vaccination activist in another country who died of brain cancer. I haven’t looked at the article yet because I know it’s bullshit. Anti-vaxxers are probably arguing that she wouldn’t have died of brain cancer if she hadn’t been vaccinated. On the surface, that’s complete nonsense. People get aggressive cancers like astrocytoma regardless of whether they’re vaccinated or not. So, I won’t buy into that, but I am open to looking at less ridiculous claims.

I delayed getting my vaccination for a month until I had a tiny tumour frozen off, just in case Lance’s lunatics were right about not wanting to distract your immune system with a vaccination when it’s trying to get rid of bad cells. My doctors said that was nonsense, but maybe it’s not. So, I try to be open to points that aren’t complete nonsense. However, I pay limited attention to what can seem like an endless flow of new nonsense from the other side.

Jacobsen: This sounds like a consequence of age and experience. Previously, in the interview with Errol Morris, you said you didn’t feel like your obsessive practicing, for instance, resulted from being any older or wiser. Do you think you’ve grown in your understanding of becoming older and wiser in a broader sense?

Rosner: I still make mistakes with my time. I’m 64. I hope I make it into my eighties or nineties, but my best years are now. I’m still lazy. So, no, I haven’t acquired better work habits. I don’t think I’ve acquired wisdom. I don’t want this conversation to be about the lessons I’ve learned so far. That, to me, seems a little horseshitty because I’m still the same person I was.

Jacobsen: What about the growth of scientific methodology and thinking, the ability to change your mind as you get more data? Is that approach to thinking about life important?

Rosner: Yes. If you’re trying to do science, and I try to do science from time to time—I should spend more time doing it—I still believe strongly in informational cosmology. But if something comes along that forces me to adapt my thinking… I don’t strongly believe you can have a universe that works without exotic dark matter. But suppose exotic dark matter were discovered conclusively. In that case, we’ve yet to detect even a single exotic dark matter particle directly. So, what would that discovery even look like?

If the matter is so dark that it doesn’t seem easily discoverable through the usual methods, how would we detect it? But I’d consider it if there was some semi-convincing evidence or even a conclusive experiment that demonstrated or indicated the possibility of dark matter. I’ve looked at informational cosmology and revised it in little spurts when I’ve had the attention to do that. It’s a bit different in certain particulars than when we started talking ten years ago and certainly different from when I started thinking about it 40-plus years ago. So yes, I’m open to change.

Rick Rosner, American Comedy Writer, www.rickrosner.org

Scott Douglas Jacobsen, Independent Journalist, www.in-sightpublishing.com

License & Copyright

In-Sight Publishing by Scott Douglas Jacobsen is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. ©Scott Douglas Jacobsen and In-Sight Publishing 2012-Present. Unauthorized use or duplication of material without express permission from Scott Douglas Jacobsen strictly prohibited, excerpts and links must use full credit to Scott Douglas Jacobsen and In-Sight Publishing with direction to the original content.

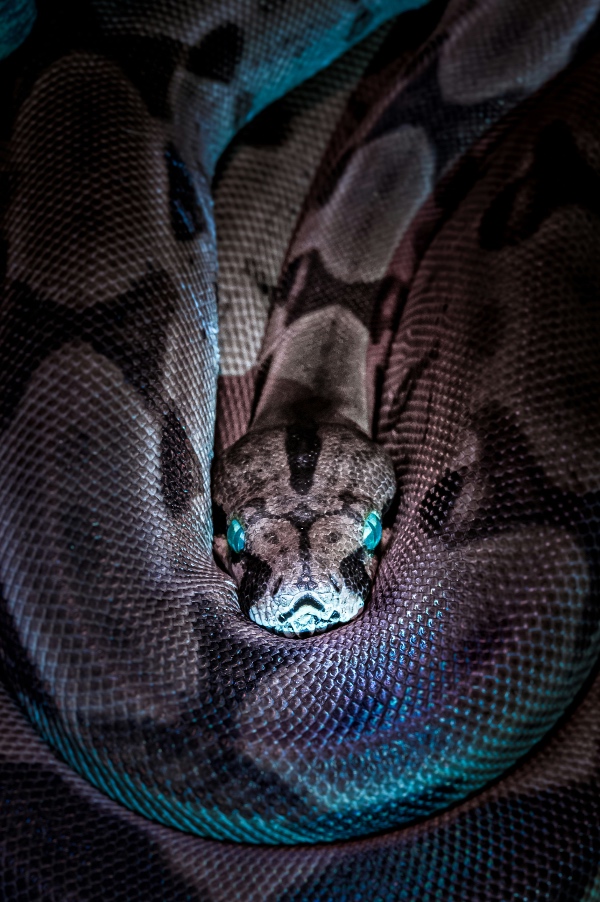

Photo by Jan Kopřiva on Unsplash