Ask A Genius 95 – Life and Death (10)

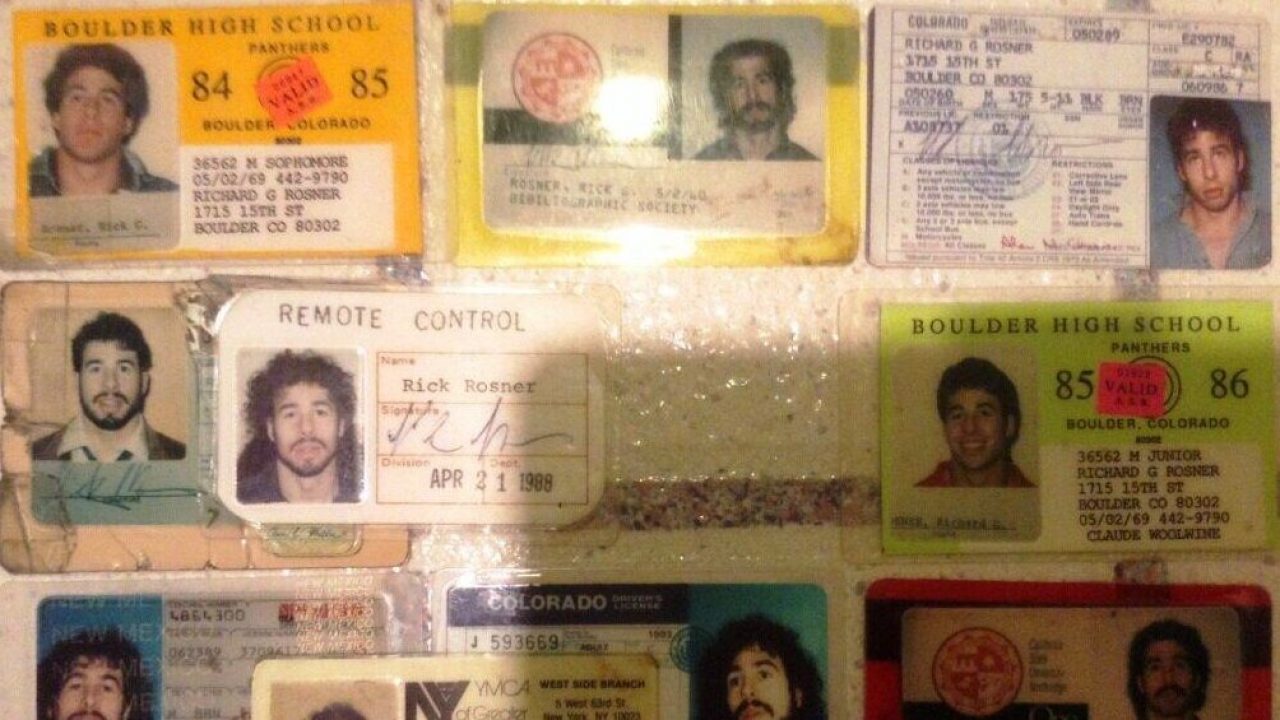

Scott Douglas Jacobsen and Rick Rosner

February 20, 2017

*Footnotes & in-text citations in the interview & references after the interview.*

*This session edited for clarity and readability.*

Rick: The last time we spoke, I had begun to read a book by Thomas Wolfe called The Kingdom of Speech (Wolfe, 2017; Amazon, 2017).[1] It is about the origin of speech in humans and how difficult it is to figure out when and why it originated (King, 2013; University of New England, 2014; Balter, 2015; Morelle, 2013; Lieberman, 2007; Polychroniou & Chomsky, 2016).[2] I said some things that were circular reasoning. I forgot what, or most of it. Before I get to any reasoning or even if I get to any reasoning, I want to set the crime scene. We are trying to figure out how speech originated, but you can’t even do that or how humans became—for most of the history of humanity, humans considered themselves separate from the animal kingdom (Choi, 2016; Wolchover, 2011; Hogenboom, 2015; University of Adelaide, 2013; Suddendorf, 2013; Stix, 2014). It is an easy conclusion to reach when you look at how different our lives are from animal lives and how different we are in abilities and physiology. We’ve got giant brains. We’ve got speech. We invent stuff. We transformed the world and pretty much taken over the world.

Before you can talk about how that happened via evolution, we kinda have to set up the pattern of facts to see what you can pull out of it. So fact one as much as I understand it is that humans have been genetically pretty much the same for the past 100,000 years. And for a couple million years before that, there were Neanderthals and a bunch of other near-human types of hominids that also had pretty big brains. I think the Neanderthal brains were even bigger than human brains. So that there were hominids with near-human capabilities. There were humans for 100,000 years. There were near-humans for a couple million years at least before that. We’ve been around for a long time. Fact two would be that as a species we have become extremely successful in the past, say, 10,000 years, which is as far back as history really reaches. There might be cave paintings that reach back. I don’t know. How far back? 30,000, 40,000, years?

Scott: Places like France, ~30,000 years ago. Other areas like Indonesia, maybe, 35,000 or 40,000 years ago.

R: We’ve never discovered animals that do representational painting. That is a mark of human near-civilization, say. It only goes back 20,000 years or so, maybe 30,000 or 40,000. Fact three is we have enormous brains compared to other animals. We have speech. We have the ability for extreme flexibility and ingenuity, and inventiveness and toolmaking. All of that stuff. So, that pretty much sets the scene. And then this book, this Tom Wolfe, The Kingdom of Speech, book talks about Noam Chomsky saying there’s a speech organ (McGill University, n.d.; McGilvray, 2009).

That somehow there’s a specialized organ in the brain, or it’s a neighborhood. I haven’t read Chomsky enough or at all. Some part of the brain evolved into specialized speech (Barsky, 2016).3 Then some other people have come along more recently that dispute that, but, in any case, speech remains – accounting for when it originated and how it evolved – a problem. 3 Universal grammar (2016) states: Universal grammar, theory proposing that humans possess innate faculties related to the acquisition of language. The definition of universal grammar has evolved considerably since first it was postulated and, moreover, since the 1940s, when it became a specific object of modern linguistic research. It is associated with work in generative grammar, and it is based on the idea that certain aspects of syntactic structure are universal. Universal grammar consists of a set of atomic grammatical categories and relations that are the building blocks of the particular grammars of all human languages, over which syntactic structures and constraints on those structures are defined. A universal grammar would suggest that all languages possess the same set of categories and relations and that in order to communicate through language, speakers make infinite use of finite means, an idea that Wilhelm von Humboldt suggested in the 1830s. From this perspective, a grammar must contain a finite system of rules that generates infinitely many deep and surface structures, appropriately related. It must also contain rules that relate these abstract structures to certain representations of sound and meaning—representations that, presumably, are constituted of elements that belong to universal phonetics and universal semantics, respectively. Barsky, R.F. (2016, September 6). Universal grammar. Retrieved from https://www.britannica.com/topic/universalgrammar.

The deal is that we been really successful. Humans have been really successful beginning 10,000 years ago. The human population really started increasing steadily from world population of a few thousand to like a quarter billion at the time of Christ to half a of a billion in the late Middle Ages and early Renaissance to 7.3 billion people now (Annenberg Foundation, 2016; World Population History, 2016). For most of the history of humans on earth, we were successful enough to survive, but we weren’t that wildly successful compared to the last 10,000 years.

So, you have to ask, “What were humans doing for the first 80% or 90% of their history on Earth?” Once you hit a certain level of civilization, it looks like things start going really fast. We went from no civilization to the first vestiges or the first traces of civilization going from hunting and gathering to farming 10,000 years ago. And then for the past 10,000 years, it’s been a steady almost inevitable-looking increase in technical ability and in human population.

Yet, we were successful enough to survive as a species for 80,000 or 90,000 years before that. And millions of years before that if you count closely related hominids as almost human enough to be humans, so I speculate that we were successful enough to survive for hundreds of thousands of years. But not so super successful because we were living like fancy apes. I would guess that humans with their super big brains used their brains as their predecessors did, but just better and more cleverly. But still having more or less the same behaviors and life strategies as apes, really clever ones; better hunters, better gatherers, maybe better at finding shelter, maybe starting to use tools, but using them for the same stuff apes did for hunting, we were super successful apes.

It took many tens of thousands of years for culture to start building up to the point where our lifestyles could sufficiently diverge from ape lifestyles and towards early human lifestyles that we eventually, 10,000 years ago, got on this accelerated ramp up to technical proficiency we have now. So, it was a slow build-up of skills until those skills, and the flexibility in behaviour, all sufficiently reinforced themselves that entirely new ways of life could be lived by the humans of 20,000 to 10,000 years ago, including language.

This book I just read discusses whether language is an artifact, which is something manufactured by humans like stone tools or bows and arrows rather than something that is innate to us because we evolved. Anyway, to go back to scene setting, we evolved big brains, didn’t build them. Probably, we evolved big brains in the context of still living like apes. By the time we began living like humans, our brains were already set at our current large size. So, the big brains came first and the human lifestyle came later, and there must’ve been – even for living as apes – evolutionary advantages sufficient to build the brains big. Brains came first and let us live successfully as apes.

Then as we built up culture, eventually, it let us diverge from ape behaviour, which doesn’t answer the question posed in this book whether language ability is an evolved trait that can be found within specific structures in the brain or whether language is a cultural artifact that takes advantage of the brain’s in-built flexibility. I can’t answer that question, but I can propose a question which reflects on that. Which is, we can assume our brain size and brain flexibility – the way our brains continuously rewire themselves via sending out a zillion dendrites found more and more ways to do things depending on patterns in the flow of thought and information – came from pressure of living as apes (Spencer, 2013). The question is “would there be any evolutionary pressure to acquire specific language capabilities?”

In other words, would being good at language provide enough of an evolutionary advantage that it’s likely that specific language abilities are hardwires into our brains or does our ability to have language rest entirely on – or close to entirely – the evolutionary advantages provided by general increases in brain size and flexibility? I think that’s where the main—we can look at brain structure and try to find specific language facilitating structures. But short of doing that, the central question of whether language is an evolved ability or a cultural artifact rests on that question. Whether language facility had its own evolutionary momentum separate from the momentum provided by increases in brain size and flexibility.

References

- Amazon. (2017). The Kingdom of Speech. Retrieved from https://www.amazon.ca/Kingdom-Speech-Tom-Wolfe/dp/0316404624.

- Annenberg Foundation. (2016). Unit 5: Human Population Dynamics // Section 4: World Population Growth Through History. Retrieved from https://learner.org/courses/envsci/unit/text.php?unit=5&secNum=4.

- Balter, M. (2015, January 13). Human language may have evolved to help our ancestors make tools. Retrieved from http://www.sciencemag.org/news/2015/01/human-language-may-have-evolved-help-our-ancestors-make-tools.

- Blaxland, B. (2016, February 5). Hominid & Hominin – What’s the Difference?. Retrieved from https://australianmuseum.net.au/hominid-and-hominin-whats-the-difference.

- Bradshaw Foundation. (n.d.). 10,000 – 8,000 Years Ago. Retrieved from https://www.bradshawfoundation.com/journey/agriculture2.html.

- Bradshaw Foundation. (2016, September 12). The Cave Paintings of the Lascaux Cave. Retrieved from https://www.google.ca/?gfe_rd=cr&ei=7IirWL8vrc_yB83cvtgE&gws_rd=ssl#q=cave+paintings+in+france.

- Choi, C.Q. (2016, March 25). Top 10 Things that Make Humans Special. Retrieved from http://www.livescience.com/15689-evolution-human-special-species.html.

- Descartes, R. (1649). Animals are Machines. Retrieved from http://journalofcocom/Consciousness136.html.

- Dowden, B. (n.d.). Fallacies. Retrieved from http://www.iep.utm.edu/fallacy/.

- Hogenboom, M. (2015, July 6). The traits that make human beings unique. Retrieved from http://www.bbc.com/future/story/20150706-the-small-list-of-things-that-make-humans-unique.

- King, B.J. (2013, September 5). When Did Human Speech Evolve?. Retrieved from http://www.npr.org/sections/13.7/2013/09/05/219236801/when-did-human-speech-evolve.

- Letzter, R. (2016, September 16). This is the most important difference between Homo sapiens and Neanderthals. Retrieved from http://www.businessinsider.com/difference-humans-neanderthals-homo-sapiens-2016-9.

- Lieberman, P. (2007, February). The Evolution of Human Speech Its Anatomical and Neural Bases. Retrieved from http://www.cog.brown.edu/people/lieberman/pdfFiles/Lieberman%20P.%202007.%20The%20evolution%20of%20human%20speech,%20Its%20anatom.pdf.

- McGill University. (n.d.). Tool Module: Chomsky’s Universal Grammar. Retrieved from http://thebrain.mcgill.ca/flash/capsules/outil_rouge06.html.

- McGilvray, J.A. (2009, September 10). Noam Chomsky. Retrieved from https://www.britannica.com/biography/Noam-Chomsky.

- Morelle, R. (2013, April 8). Primate call gives clues to human speech o Retrieved from http://www.bbc.com/news/science-environment-22067192.

- New World Encyclopedia. (2008, April 2). Hominid. Retrieved from http://www.newworldencyclopedia.org/entry/Hominid.

- Polychroniou, C.J. & Chomsky, N. (2016, September 24). On the Evolution of Language: A Biolinguistic Perspective. Retrieved from https://chomsky.info/on-the-evolution-of-language-a-biolinguistic-perspective/.

- (2017, January 17). Circular Reasoning. Retrieved from http://rationalwiki.org/wiki/Circular_reasoning.

- Rousseeuw, P.J. & Leroy, A.M. (1987) Robust Regression and Outlier Detection. Wiley, p. 57. Retrieved from http://mste.illinois.edu/malcz/DATA/BIOLOGY/Animals.html.

- Rips, L.J. (2002, July 10). Circular Reasoning. Retrieved from http://www.psychology.northwestern.edu/documents/rips-circular-reasoning.pdf.

- Rogers, N. (2015, May 21). Alzheimer’s origins tied to the rise in human intelligence. Retrieved from http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/evolution/are-we-still-evolving.html.

- Smithsonian Institution. (2017a, February 20). Human family Tree. Retrieved from http://humanorigins.si.edu/evidence/human-family-tree.

- Smithsonian Institution. (2017b, February 20). Neanderthals: larger eyes and smaller brains. Retrieved from http://humanorigins.si.edu/research/whats-hot-human-origins/neanderthals-larger-eyes-and-smaller-brains.

- Smith, S.L. (2013). Evidence that dendrites actively process information in the brain. Retrieved from http://www.kurzweilai.net/evidence-that-dendrites-actively-process-information-in-the-brain.

- Stix, G. (2014, September). What Makes Humans Different Than Any Other Species. Retrieved from https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/what-makes-humans-different-than-any-other-species/.

- Stromberg, J. (2013, March 12). Science Shows Why You’re Smarter Than A Neander Retrieved from http://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/science-shows-why-youre-smarter-than-a-neanderthal-1885827/.

- Suddendorf, T. (2013, September 21). Are we really different from animals?. Retrieved from http://www.cnn.com/2013/11/21/health/animals-humans-gap/.

- Tuttle, R.H. (2015, October 16). Human evolution. Retrieved from https://www.britannica.com/science/human-evolution.

- Tyson, P. (2009, December 14). Are We Still Evolving?. Retrieved from http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/evolution/are-we-still-evolving.html.

- University of Adelaide. (2013, December 4). Humans not smarter than animals, just different, experts say. Retrieved from https://phys.org/news/2013-12-humans-smarter-animals-experts.html.

- University of New England. (2014, March 2). Talking Neanderthals challenge the origins of speech. Retrieved from sciencedaily.com/releases/2014/03/140302185241.htm.

- University of Oxford. (2013, March 19). Neanderthal brains focused on vision and movement leaving less room for social networking. Retrieved from sciencedaily.com/releases/2013/03/130319093639.htm.

- Wilford, J.N. (2014, October 8). Cave paintings in Indonesia May Be Among Oldest Known. Retrieved from https://www.nytimes.com/2014/10/09/science/ancient-indonesian-find-may-rival-oldest-known-cave-art.html?_r=0.

- Wolchover, N. (2011, July 3). What Distinguishes Humans From Other Animals?. Retrieved from http://www.livescience.com/33376-humans-other-animals-distinguishing-mental-abilities.html.

- Wolfe, T. (2017). About Thomas Wolfe. Retrieved from http://www.tomwolfe.com/bio.html.

- World Population History. (n.d.). World Population History. Retrieved from http://worldpopulationhistory.org/map/1/mercator/1/0/25/#.

Footnotes

[1] About Thomas Wolfe (2017) states:

Tom Wolfe was born and raised in Richmond, Virginia. He was educated at Washington and Lee (B.A., 1951) and Yale (Ph.D., American Studies, 1957) universities. In December 1956, he took a job as a reporter on the Springfield (Massachusetts) Union. This was the beginning of a ten-year newspaper career, most of it spent as a general assignment reporter. For six months in 1960 he served as The Washington Post’s Latin American correspondent and won the Washington Newspaper Guild’s foreign news prize for his coverage of Cuba.

In 1962 he became a reporter for the New York Herald-Tribune and, in addition, one of the two staff writers (Jimmy Breslin was the other) of New York magazine, which began as the Herald-Tribune’s Sunday supplement. While still a daily reporter for the Herald-Tribune, he completed his first book, a collection of articles about the flamboyant Sixties written for New York and Esquire and published in 1965 by Farrar, Straus, and Giroux as The Kandy-Kolored Tangerine-Flake Streamline Baby. The book became a bestseller and established Wolfe as a leading figure in the literary experiments in nonfiction that became known as New Journalism.

Wolfe, T. (2017). About Thomas Wolfe. Retrieved from http://www.tomwolfe.com/bio.html.

[2] Human language may have evolved to help our ancestors make tools (2015) states:

If there’s one thing that distinguishes humans from other animals, it’s our ability to use language. But when and why did this trait evolve? A new study concludes that the art of conversation may have arisen early in human evolution, because it made it easier for our ancestors to teach each other how to make stone tools—a skill that was crucial for the spectacular success of our lineage.

Researchers have long debated when humans starting talking to each other. Estimates range wildly, from as late as 50,000 years ago to as early as the beginning of the human genus more than 2 million years ago. But words leave no traces in the archaeological record. So researchers have used proxy indicators for symbolic abilities, such as early art or sophisticated toolmaking skills. Yet these indirect approaches have failed to resolve arguments about language origins.

Balter, M. (2015, January 13). Human language may have evolved to help our ancestors make tools. Retrieved from http://www.sciencemag.org/news/2015/01/human-language-may-have-evolved-help-our-ancestors-make-tools.

Author(s)

Scott Douglas Jacobsen

Editor-in-Chief, In-Sight Publishing

Rick Rosner

American Television Writer

License and Copyright

License

In-Sight Publishing and In-Sight: Independent Interview-Based Journal by Scott Douglas Jacobsen is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at www.in-sightjournal.com and www.rickrosner.org.

Copyright

© Scott Douglas Jacobsen, Rick Rosner, and In-Sight Publishing and In-Sight: Independent Interview-Based Journal 2012-2017. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express and written permission from this site’s author and/or owner is strictly prohibited. Excerpts and links may be used, provided that full and clear credit is given to Scott Douglas Jacobsen, Rick Rosner, and In-Sight Publishing and In-Sight: Independent Interview-Based Journal with appropriate and specific direction to the original content.

Pingback: Ask A Genius 95 – Life and Death (10) | In-Sight Publishing